Escape from the Workhouse (Bicester)

The Slightly Secret Six Escape from the Workhouse, not by Enod Blytin – being a narrative of Bicester's very own Oliver Twists

By Mark [Guest Contributor to The Bicestorian]

The solitary figure adjusted his overcoat against the winter chill as he made his way along the

street in Bicester. There was no need. The briskness of his pace and the determination in his

step would have generated sufficient heat to warm him on his journey. The body language

betrayed the fact that this was not a man out for a casual stroll, but this was someone going

somewhere on important business. When all parties had arrived on that 17th of January 1860, they

were six in number, and represented a cross section of Bicester’s ‘establishment’. They were: Sir

Henry Peyton of Swift’s House and Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Bicester Union,

William Tubb, Vice-chairman of the Board, of the Bicester banking family, Rev. William John Dry, an

alumnus of Wadham College in Oxford who matriculated on the 30th of January 1839, getting his B.A.

in 1843 and his M.A. in 1845 he was now Vicar of St Mary’s at Weston-on-the-Green from 1854 until

his death on 30th of April 1877, Charles Fowler, local farmer of 370 acres employing eleven men and

five boys, Richard Gibbs Palmer, a local draper living on the Market Square and able to employ two

shop assistants and two domestic servants, and William Reynolds, a farmer of 120 acres and

employing five men and one boy.

This was not an impromptu gathering but had been called together by the Board on the 13th

of January to discuss matters relating to members of Bicester’s society far removed socially from

themselves, the residents of the Bicester Union Workhouse, and one very specific matter. It had

taken place thirteen days before their meeting, on the 4th of January. On that day William Dagley,

Edward Walker, Robert Carey, Barnett Cross and brothers Solomon and Caleb Smith, boys in the care

of Bicester’s Union Workhouse, “…appeared before the Board for having on Wednesday morning last

absconded from the Union Workhouse.” Apparently, the Porter had unlocked the door to the boys’

room at about 7 o’clock that morning and shortly afterwards they had gone downstairs and had got

over the wall. What were the circumstances that had prompted them into this course of action?

According to the Board minutes [Oxfordshire History Centre reference PLU2/G/1A1/11], Alfred

Harris, the schoolmaster, the boys had been tutoring an unnamed individual – there is a gap in the

text of the minutes as if deliberately left for the insertion of a name at a later date, something that

was never done – to kick the schoolmaster’s shins, and that they had run away to avoid being

punished for this offence. The Schoolmaster knew that the boys had absconded ten minutes after

the event but inexplicably took no action to get them back. Similarly, the Porter did not take any

steps to get them back or inform the police to avoid the expense of looking after them. The

escapees’ freedom did not last long – they were brought back to the Workhouse at noon the

following day.

The text of the report [Oxfordshire History Centre reference PLU2/G/2A1/5] of the

committee set up to investigate the circumstances of the escape is included in the Board’s minutes of

27th of January. The relevant section reads as follows.

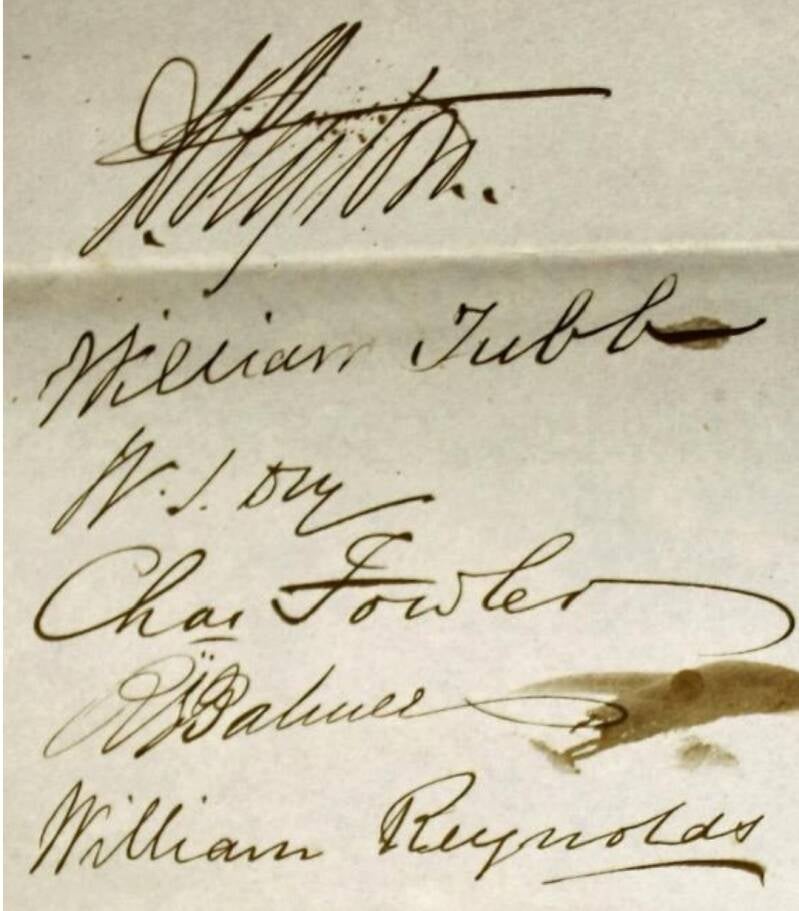

“We the undersigned guardians forming the Committee on Friday the 13th instant to

investigate the case of the boys escape from the Workhouse on January 4th instant beg to

make the following report namely.”

“That we are of opinion that there is no reason whatever for the children running away.”

“Facilities of escape have been given which are now removed.”

“The conduct of the Schoolmaster in not reporting the escape of the boys for three quarters

of an hour after their escape the committee think censurable. The Committee are of opinion

that the Governor when appraised of the escape of the children should have taken

immediate steps for their recovery.”

The remainder of the report goes on to

address the question of a stable at the Workhouse

being used as a ward for tramps. The report was signed

by all the members of the Committee (right) – ink

smudge as on the original.

As regards the punishment for the escapees,

the Board “Resolved that Edward Walker and [William]

Dagley do have 4 stripes with a cane with an additional

lesson for one week the other boys an additional

lesson for one week.” Would the punishment for

tutoring someone “to kick the schoolmaster’s shins”

have been any worse?

The Schoolmaster, who appeared before the

Board, was reprimanded for his tardiness in reporting

the escape to the Master, and that this should have

been done immediately that he knew that the six had

absconded; certainly not three quarters of an hour

after the event.

Any embarrassment that the Workhouse authorities may have felt over the escape was

perhaps lessened by the fact that the matter was all kept ‘in house’, with neither of the Bicester

newspapers carrying a report about the escape and its aftermath.

So, what do we know about the lives of the fleeing six before and after their escape from the

Bicester Union Workhouse, above [OHC reference POX0646855]. Thanks to mid to late Victorian

bureaucracy and record keeping, in some instances, quite a bit. To take the six in the order in which

they appear in the Board’s minutes:

William Dagley – is somewhat of an enigma. The Dagley surname does not appear in either

the 1851 nor the 1861 Census returns for the Bicester Union Workhouse, leaving us with the

possibility that they may have arrived and left sometime during the intervening decade and thus

have been missed by both. There is a William Dagley whose birth was registered during the second

quarter of 1846, the son of George, a labourer, and Mary, and who was baptised at St Mary’s in

Launton on the 11th of November that year. A clue as to what may have driven the family to the

workhouse comes in the registers of the church of St Mary and St Edburga in Stratton Audley. On the

3

rd of March 1856 it records the burial of Mary Dagley, from Caversfield, aged 43. George is still alive

and would go on to marry Hannah Moore in 1868. He would go on to live to a ripe old age before

being laid to rest on the 29th of March 1902, aged 85, at Stratton Audley. As a widower, could raising a family on a labourer’s wages have been too much for him? The 1851 Census reveals that William

has two older sisters: Elizabeth, 11, and Mary, 7, and that the family are living in Launton. A decade

later, 1861, and a year after the ‘escape’ William, now 15, is recorded as working as a carter’s boy for

Thomas Hirons, of Old Field Farm, of 214 acres near Stratton Audley, and employing four men. In

1871 he is recorded as being an agricultural labourer working for his grandfather, Philip Dagley, at

Dagley’s Court near Stratton Audley. He would go on to marry Elizabeth Carey on the 3rd of August

1875 in the church of St Mary and St Edburga in Stratton Audley, and by the time of the 1891 Census

their union has been blessed with three children: Florence, Sarah, and William. He was laid to rest in

this same church on the 28th of December 1916, aged 70, having worked on the land all his adult life.

The caveat is that apart from the name matching, his age and location being close, there is no

irrefutable link between this William Dagley, and the William Dagley who escaped from the

workhouse.

Edward Walker – was born in Bicester and sadly in the 1851 Census we already find him,

aged three, and six other members of his family: Mary Ann 15, Sarah 12, Charlotte 11, John 9, Susan

7 and Charles 5, in Bicester Workhouse as indoor pauper scholars. The tragedy of his situation is that

ten years later, in the 1861 Census, he is still listed as being in the Workhouse as a scholar, although

none of his siblings are listed on the Census return.

Robert Carey – was born in Launton and in the 1851 Census he is living aged 3, with his

parents, Thomas, 32 from Stratton Audley and Mary, 27, from Launton. Sadly, the 1861 Census has

Robert in the Workhouse where, in the column asking for his relation of the family, he is described as

a “pauper”. But he was not destined to remain there, or even in Bicester. A decade later, in 1871, he

is living in Penge, working as a railway plate layer, with his wife Lucy and six-month-old son Thomas.

He and Lucy Mumford, from the hamlet of Blackthorn, in the parish of Ambrosden, had married in

the Dissenting Chapel in Bicester in the spring of 1869. Were William Dagley’s wife, Elizabeth Carey,

and Robert Carey related? The Carey surname appears in the Stratton Audley area over many

generations. Working backwards along their respective lines of descent for five generations from

Elizabeth, and four generations from Robert, both lines meet at one George Carey, who was born on

the 27th of September 1698, in Stratton Audley. So, yes, they were very distantly related – they were

nth cousins, umpteen times removed.

Barnett Lot Cross – was born in Fritwell on the 6th of May 1847 and was baptised on the 8th

of July 1849; his father’s occupation is given as “policeman”. Eden Cross and Sarah Shelton had

married on the 23rd of October 1843, in the parish of St Paul’s, in Deptford. Eden’s occupation then

being given as “fell monger”, a dealer in hides and skins, particularly sheepskins, and who might also

prepare skins for tanning. Eden was a local man; he had been baptised on the 11th of March 1818 in

St Mary’s Church in Charlbury, the son of Henry, a labourer (a farrier on Eden’s wedding record), and

Eunice Cross of Finstock. Both Eden and Sarah were living in Deptford at the time of their wedding. In

the 1851 Census Barnett is aged 3, with his parents, and older brother Henry Charles, the family

having moved to Enstone. Sadly, by the 1861 Census, Barnett is listed as being a scholar in the

Workhouse. The reason for this may have been a double tragedy that had occurred in the intervening

decade. On the 12th of January 1853 Eden Cross was laid to rest at St Kenelm’s Church, in Enstone.

Just over two years later, on the 17th of January 1855, Sarah Cross was, in her turn, laid to rest at St

Giles’ Church, in Camberwell. Interestingly, in the record of Sarah’s burial, her place of residence is

simply given as “workhouse”; it seems that the family were already on hard times, having lost its

breadwinner – a reminder, as if one were needed, of how fragile life was before the coming of the

welfare state, with many living just one step away from the workhouse. Rural poverty was very real.

Barnett would have been seven at the time and with Henry Charles just ten, and both orphaned, it is

not surprising that the workhouse beckoned for them, if they were not there already. Barnett Cross

passed away at about 7.10 p.m. on the 21st of January 1866 from valvular disease of heart, at St

George’s Hospital in London, having been admitted there on the 23rd of December the previous year,

under the care of Dr Henry Pitman; he had been working as a messenger and was just nineteen years

old. His medical record, written by Reginald Thompson, begins as follows.

“Had suffered for 4 years from rheumatism, the attacks recurring frequently. The attack for

which he was admitted was of 1 week’s standing. He complained principally of pains in the

chest & hands. No distinct history of [?] but early deaths of father and mother. On admission

there was an endocardial murmur heard …”.

On his final day, he complained of much cardiac pain. From the afternoon and into the

evening he was seized with sudden orthopnea, shortness of breath that occurs while lying flat, and is

relieved by sitting or standing. He was then suffering from acute pains between the shoulders, with

cramps in the legs as well as great dyspnea, again shortness of breath, his pulse rising to 140. He “…

died quite suddenly in about two minutes at 7.10 p.m.”

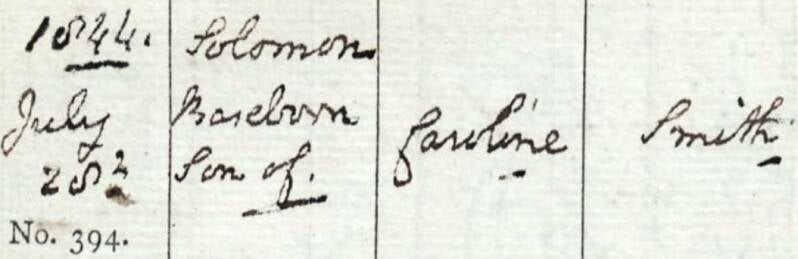

Solomon Smith – was

born in Upper Heyford on the

30th of April 1844, the son of

Caroline Smith, 33, born in

Middleton Stoney, and was

baptised in St Mary’s church in

Chesterton on the 28th of July of

the same year. He is described

as “Baseborn son of…”, that is he was born out of wedlock, and there is no father’s name in the

register. He was not unique in this respect. Out of the sixteen baptisms celebrated at Chesterton

between July 1844 and July 1845, four, including Solomon, are described as being “baseborn” with

no father’s name in the register. Caroline, a single mother, is described as a labourer. Solomon Smith

married Sarah Dipper in Bicester, in April 1870 when he was 26 years old.

Caleb Smith – was born in Chesterton to Caroline Smith in the final quarter of 1849 and

baptised on the 11th of November that same year in the Norman font at St Mary’s church. He also

appears to have been illegitimate – there is no father’s name next to his name in the baptismal

register. His entry in the register shows evidence something having been erased – possibly also

describing him as being “baseborn”. In the 1851 Census he is living with his mother and two older

siblings, Abel, and Solomon in Chesterton. Caroline is described as a char woman and Abel, despite

only being 11 years old, is already working as an agricultural labourer.

We do not have pictures of any of the six escapees, but (if the

reader will forgive a slight digression) we do have one of Solomon’s and

Caleb’s elder brother Abel; but one taken for all the wrong reasons, and not

one that you might want to put in the family album (right). It is included in

a collection of images of prisoners serving time in Oxford Goal, in Abel’s

case this was taken on the 24th of September 1870 when he had been

convicted of stealing three fowls. This was not his only encounter with the

law and he appears to have been convicted for a series of mostly minor,

petty offences: 15th July 1859 – assault on Sarah Sims, 7th June 1861 –

trespass in pursuit of game, 19th July 1861 – stealing partridge eggs, 23rd

July 1863 – riding a timber carriage with no other person to hold the reins,

24th November 1865 – using a snare for the purpose of killing game, 6th

April 1866 – stealing eggs, 29th June 1866 – stealing fishing lines, and, at an

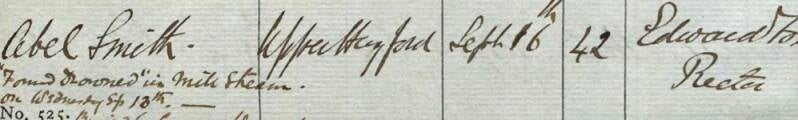

unrecorded date – for stealing tame rabbits. The paperwork relating to Abel Smith’s misdeeds can be found at the Oxfordshire History Centre at “QS” series of the

proceedings of the Oxfordshire Quarter Sessions for the relevant year. Abel Smith was laid to rest at

St Mary’s Church in Upper Heyford on the 16th of September 1882, he was 42 years old. Below the

entry for his funeral in the burial register (above) someone has added the following note about his

somewhat mysterious death; “’Found drowned’ in Mill Stream on Wednesday S[e]p[tember] 13th – buried by a coroner's warrant.

Create Your Own Website With Webador