Opening a Blocked Door (St Edburg's Church, Bicester)

"Opening a blocked door" – being an account of the school founded by the Reverend Samuel Blackwell

in the Church of St Edburg’s, Bicester.

By Mark [Guest Contributor to The Bicestorian]

Part way along the outside of the north

wall of Saint Edburg’s church, towards its

eastern end, there are the easily

overlooked remnants of a long since

blocked doorway, its presence now only

revealed by an archway of rough-hewn

stonework set in the wall. The inside of the

doorway has long since disappeared under

plaster and paint. This is all that remains of a

17th century school founded be the then vicar

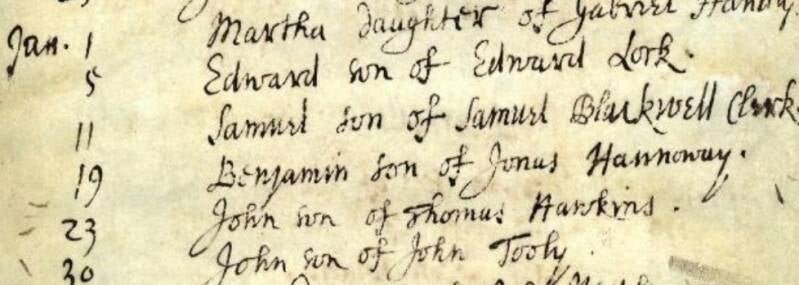

of Bicester, the Reverend Samuel Blackwell [see first image below].

Samuel Blackwell was born on the 10th of

January 1642-3 in Northamptonshire, in the

village of Moreton Pinkey, a place that Arthur

Mee describes in his “The King’s England”

volume on the county as; “…its street, winding

like a capital S, is set with pleasing old houses

of the 17th and 18th centuries, high gabled and

built with alternate layers of brown and grey

slate. One was built in the year Shakespeare

died, and many have delightful thatched roofs,

such as those clustering about the upper and

lower greens.” He was the son of Walkadine

and Marie [?] and was baptised in the simple,

round Norman font in the church of St Mary

the Virgin in the village on the 8th of December

1642, a church that Arthur Mee describes as

having; “… a square tower with thin columns

rounding the edges of its two stages, and one

of the loveliest chancels in the country, so

faithfully restored that the original design of

the early builder has been practically

reproduced. It was chosen by Cardinal

Newman as a model for the church he built at

Littlemore in Oxfordshire. Light and graceful

and of great beauty, it has three perfect lancets

in the east window, deeply splayed lancets in

each wall, and an elegant double piscina. A

wide stone ledge right across the east end is

banked for Easter Sunday with golden daffodils

massed like sunshine against the stone

background. The 700-year-old arcades spring

from Norman pillars and during the 15th

century clerestory was added.”

On the 21st of March 1661, aged 18, he

matriculated, officially became a member, of

Oxford University. Studying at Lincoln College

he obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree four

years later adding his master’s degree in 1667-

8 and supplementing these by a Bachelor of

Divinity degree in 1682.

During his studies, he was ordained on the 22nd

of August 1668, and also found time to marry

Mary Pettie at St Mary’s in Great Milton in

1674. Under the patronage of Sir William

Glynne, Samuel Blackwell was inducted Into St

Edburg’s on the 16th of August 1670. During his

time at Bicester he and Mary had six children,

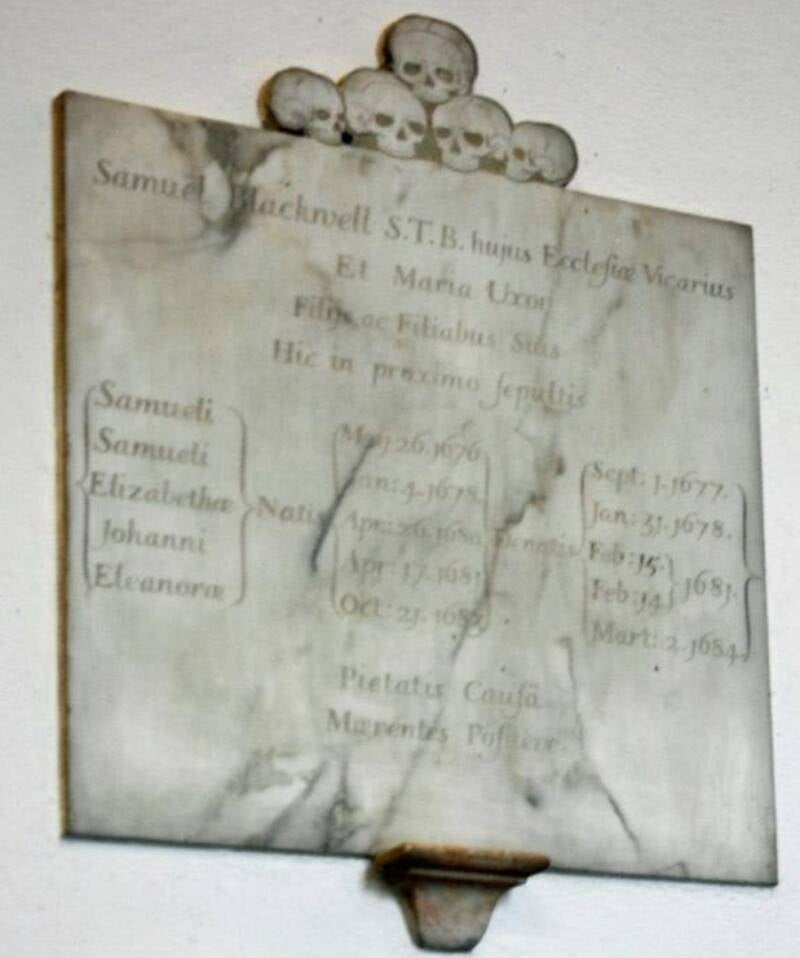

of whom, tragically, five died in infancy: Samuel

born 26th of May 1676 died 1st of September 1677, a second Samuel born 4th of January

1678 baptised on the 11th of January, entry

from the register below, died 31st of January

1678, Elizabeth born 26th of April 1680 died

15th of February 1681, John born 17th of April

1681 died 14th of February 1681 (the date

discrepancy being caused by the new year then

beginning on the 25th of March, he was actually

10 months old when he died), and Eleanor

born 21st of October 1683 died 2nd of March

1684. Only their second child, Mary, baptised

on the 13th of November 1677, survived.

A poignant memorial to the five dead children,

including a depiction of five skulls, can be

found in the chancel of the church to the left of

the altar rails [see third image below]. John and his sister

Elizabeth were buried on the same day.

Samuel Blackwell remained in Bicester until

November 1691. He was subsequently rector

at Bolton, in County Durham, and Brampton

Ash, in Northamptonshire. In September 1719

he was appointed as a prebendary at

Peterborough Cathedral by the then Bishop,

White Kennett, a name well known amongst

Bicester local historians. Samuel Blackwell

passed away and on the 5th of April 1720 was

buried at St Mary's at Brampton Ash.

During his time at Bicester, in about 1669, the

reverend gentleman founded the school for

which he is best remembered. What was the

state of education of Bicester’s children before

that date? It seems that Bicester Priory almost

certainly had a role to play. We get a hint from

the visitation on the 28th of May 1445 by the

Lord William Alnewyke, Bishop of Lincoln, in

the nineteenth year of his consecration and the

ninth of his translation – at that time Bicester,

and Oxford itself, were part of the huge

Diocese of Lincoln; the Diocese of Oxford only

being created after Henry VIII’s break with

Rome. In that, Brother John Burcestre, the sub-

prior… “says that the sons of two gentlemen,

to wit Lawis and Purcelle, are nurtured and

instructed in the house: whether at its (the

house’s) or at their parent’s cost is unknown.

The prior was enjoined not to maintain the

sons of noblemen or powerful folk at the costs

of the house.” The schoolmaster was probably

a chantry priest from the parish church. Sadly,

details of the measures taken to educate the

children of Elizabethan and early Stuart

Bicester have not come down to us and there

is a gap in our knowledge covering these years.

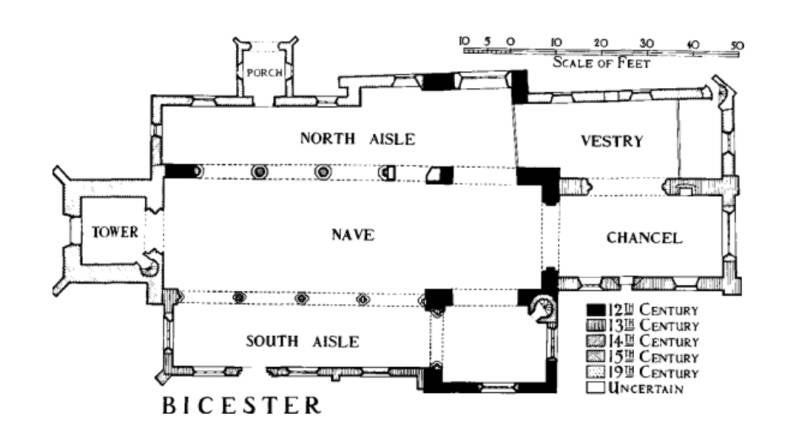

To accommodate his new school, the reverend

Samuel Blackwell choose to convert what

might have been a Lady Chapel at Saint

Edburg’s church (marked “vestry” in the below

diagram). The date of the building of this part

of the church is possibly 14th century with it

being built at the same time as the north aisle

and its identification as a Lady Chapel is based

on the importance attached to veneration of

the Blessed Virgin Mary during the Middle

Ages.

The Oxfordshire Historic Churches Trust

lists about 60 churches dedicated to the Virgin

Mary within the county and Catholic England

was sometimes referred to as “Mary's Dowry”.

One way of expressing this devotion was to build the Lady Chapel as close as possible, if

not adjacent, to the high altar of the church.

Following the Reformation devotion to the

Virgin Mary declined, although out of custom

many of the mediaeval churches kept their

dedication. In preparation to house the new

school the arches between it and the main

body of the church were filled in, the now

blocked doorway cut through the north wall

and an upper room to house the library was

constructed, this being accessed by a still

existing doorway at the north-east corner of

the church (below), that previously may have

led to quarters for a sacristan or sexton.

John Dunkin describes the school as follows,

italics as in the original text; “The building

adjoins the north side of the chancel, and is

continued from the north aisle of the church,

into which there is an entrance. It appears of

later erection than the other parts of the

fabric; so at what time is unknown: but most

probably soon after the Reformation. The

inside is filled up with desks and other

conveniences. Over it is a room formerly used

as a library, and containing a number of books,

some of which are valuable; the catalogue

remains in the hands of Mr Markland. The

school is generally thought to have been

endowed, though every writing relative

thereto is said to be entirely lost. In the Magna

Britannia it is called a Free school, “supposed

to be founded by Simon Wisdome, “an

alderman of this town, but, the writer adds, we

have no other grounds for our supposition than

he is found to have given constitutions and

orders for the government of it in the

thirteenth year of the reign of Queen

Elizabeth.””

“The school appears to have been placed

under the immediate direction of the vicar,

though at what time it ceased to be a free

school is uncertain. The name of Kennett

appearing in the list of benefactors in the

catalogue of books given for the use of the

scholars seems to indicate that it had not

ceased to be such at the time when that

gentleman assisted Mr Blackwall [sic] both in

the duties of the school, and the church; and

even the bare reflection of our present

ignorance of this institution is sufficient to

provide the greatest regret, that anything

should have ever arisen to prevent the

industrious, learned, and pious author of the

Parochial Antiquities from continuing the

excellent work done down to his own time.”

The school gained an excellent reputation

offering a classical education and was much

used by the local gentry. Among these was the

Verney family of Claydon House at Middle

Clayton in Buckinghamshire. As long as the

Reverend Blackwell managed the school, the

Verney family were as content to send their

children there as to Eton, Winchester or

Westminster. The two boys in question were

Ralph and Edmund Verney who attended the

school between 1679 and 1682 being aged

about 13 and 11.

However, by March 1679 all was not well at the

school. On the 24th of March the boys’ father

Edmund wrote to their grandfather Sir Ralph

Verney regarding the illness that had befallen

the reverend Blackwell. The letter runs as

follows, the spelling in this and the following

letters has been modernised.

“Mr Blackwell the schoolmaster at Bicester lies

in great danger of death, and all his scholars

run up and down like scattered sheep without

a shepherd, doing that which is righteous in

their own eyes, having neither tutor nor usher

to govern nor teach them, the master having

not kept an usher since Christmas and having

been sick this fortnight, so my coach brought home my sons and Mr Duncomb’s last

Saturday, and they are very well God be

thanked; but it is a pity that they should be so

much neglected, and that they should lose so

much of their time.”

This was followed two days later by a second

communication,

“I sent my man Wood to Bicester to see how

Mr Blackwell did, there is some hope of his life

now, but his recovery will be tedious and long,

in the meantime there is no usher, and the

scholars are all dispersed, and the school is

spoiled, and my children lose their precious

time, and forget more in a week than they can

get in a month, which is a grand trouble to me.

Mrs Blackwell says an usher is sent for, and

when he is come, I shall have notice of it, but

that doth not satisfy me.”

The usher was duly appointed, and Ralph and

Edmund apparently returned to Bicester.

However, all was not well at the school, as a

letter of the 10th of April relates.

“Mr Blackwell mends but very slowly and the

usher talks of going away very suddenly; the

truth of it is Mrs Blackwell is a so greedy and

covetous, that she will not allow any usher

reasonable hire, neither are my children so

carefully ordered as at first; therefore I take

that the school to be grown worse, and have

thoughts to remove them ere it be long to

Eton, Winchester or Westminster. Winchester I

know, and like very well, but only it is a place at

a great distance from me: I do intend as soon

as fine weather comes in, to go to Eton myself,

that I may satisfy myself in ye place.”

Eventually Ralph did go to Winchester, but not

before he and Edmund had spent two more

years at Bicester. The reverend Blackwell’s

recurrent belts of illness we're not the only

medical problem facing the school. At about

this time Ralph expressed a desire to come

home because there was an outbreak of

measles in the school and smallpox in the

house next door. He was advised not to be

afraid, for that was pusillanimity. To quote one

further letter, from Ralph to his father dated

28th of May 1679. It is included because of the

extraordinary deferential manner that the

writer adopts when all he is basically saying

“come and pick me up so that I can go home for

the holidays” unquote. The original letter is

written in a most elaborate hand and possibly

was dictated by the reverend Blackwell and

took care that it should be a favourable

specimen of the writer’s calligraphy.

“Most honoured father,”

“These few lines are to let you understand that

we break off one Saturday next, and I humbly

beseech you to send for us home that day that

we may a little refresh ourselves after our hard

study and we present our humble duties to

yourself and to my mother and grandfather

and our loves to my sister.”

“I subscribe myself.”

“Your dutiful son.”

“Ralph Verney.”

Nor was this a unique occurrence. On the 14th

of August 1681 Ralph again writes to his father,

this time requesting a new Bible, as the one he

has is disintegrating. He again begins “most

honoured father” but is this time “your most

dutiful and obedient son”. However, this

brought about a rebuke from his father dated

1st of September 1681.

“Child”

“Since I came home I received your long Epistle

about a new Bible with Common Prayer

Apocrypha and Singing Psalms to which (if you

want) your master may buy you, and I’ll repay

him, but methinks you tear your books too

much, and very careless of them, which is an ill

sign.”

“You write truer English than you did, but not

true enough by a great deal; and then you

make up your letters always in the ugliest

fashion that ever was for I cannot open them

without tearing out some of the written.”

One of the ushers at the school was local

historian White Kennett. He left the school in

1685 on being presented to the vicarage of

Ambrosden by Sir William Glynne. Kennett and

Blackwell remained in contact with the former

the highest regard for the latter. When, in

1691, Blackwell was promoted to the rectory of

Brampton in Northamptonshire, White

Kennett would send him proofs of his Parochial

Antiquitiesfor criticism. And when Kennett was

consecrated Bishop of Peterborough in 1718

the following year, he appointed Blackwell as a

Canon of the cathedral.

Following Samuel Blackwell’s departure his

successors kept the school running into the following century. His successor at Bicester was

Rev Thomas Sherwring who in 1692 compiled

a catalogue of the school's library as well as

endowing it with a further gift of books. The

catalogue, a large folio notebook, bound in calf,

lists 150 titles from 71 donors. The catalogue

lists donations from 1669 to 1699 and it is

interesting as it indicates the character of

books deemed necessary for a scholastic

library as well as the energy of its earliest

masters. There are many local names amongst

the donors which testifies to the reputation of

the school in the neighbourhood. It is perhaps

no surprise that the first name listed in the

catalogue of donors is that of John Coker. The

catalogue is reproduced in the 1907 Reports of

the Oxfordshire Archaeological Society. Samuel

Blackwell had taken great pains in the

formation of a library for his school and

obtained gifts of books from many members of

his own college from other Oxford friends as

well as from pupils and their relations. Each

book appears to have been bound in calf, and

most had a brass ring for a chain fastened by a

clamp to one of the lids with the donor's name

being written in Latin on the first blank page.

The library appears to have been in existence

until the restoration of the Bicester church in

1862 and had been kept in a parvise over the

porch which served as a muniment room.

Sadly, the books were considered useless and

after some time were disposed for a trifling

sum. Some of them fell into the hands of a

London bookseller, whose catalogue of 1896

announces that he was selling “Thirteen books

from the library of Schola Bucestrenis, Oxon,

fitted with brass rings belonging to the chains

to which they were formerly attached; with a

record in most instances of the donors name.

The plain binding and calf has in the case of

some of the books suffered severely, as might

be expected from the chaining system and

probably from the forcible abstraction of the

brass chains. The rings however are all in good

condition and establish the existence of

chained books in a Library of the XVIIth

century, and one which was unknown to Mr

William Blaydes, as it is not referred to his in

enumeration of chained libraries.”

In 1907 eight books from the library are

recorded as still being in Bicester, in a

muniment chest of the church. In each case the

binding and ring are described as being in

excellent condition, although some contents

are imperfect.

Sadly, the drive and enthusiasm of Samuel

Blackwell and Thomas Sherwring did not pass

down to their successors and the school

appears to have gone into a period of decline.

Following the opening of Saint Edburg’s School

in 1859 the alterations made by Reverend

Samuel Blackwell to accommodate his school

were removed returning the schoolroom back

into parish use. At about the same time the

doorway in the north wall was bricked up.

Reverend Samuel Blackwell’s schoolroom as it

is today. The blocked-up doorway in the north

wall would have entered below the monument

to the Carver family, related by marriage to

White Kennett, on the wall. This had been on

the chancel wall but was relocated when the

wall dividing the schoolroom from the main

body of the church was taken down.

Create Your Own Website With Webador